- Fool of Swords Newsletter

- Posts

- Reevaluating Italian Rapier and Dagger

Reevaluating Italian Rapier and Dagger

Have We Been Doing It Wrong?

I’ve been fencing rapier for a long time and have had the absolute pleasure to cross swords with all sorts of folks. One of the main trends I have noticed, particularly when it comes to rapier and dagger, is, to overly simplify things, that there are people who pride themselves on being “by the book” and that there are folks who explicitly don’t. Now yes, there are obviously people in the middle who maybe look at a book sometimes or work with a teacher who spends some time with the manuals, but we’re going to leave that group out of the picture for now.

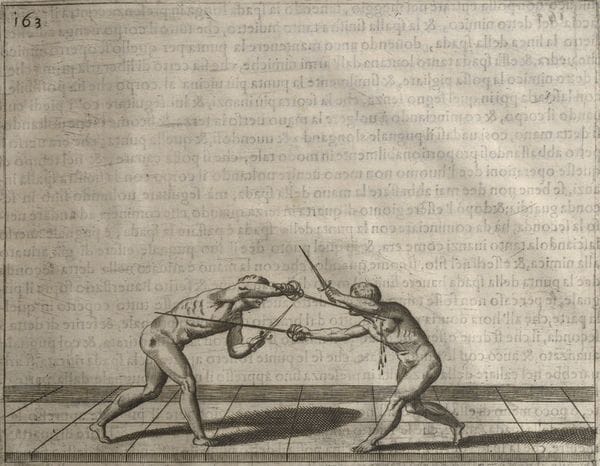

The result of this split is the “by the book” folks saying that the sword is your primary defense and your dagger is there as a backup. At the same time, the fighters who aren’t as interested in history tend to treat the dagger as the main form of defense, freeing up the sword to attack. The default way we teach it going by the book is some variety of “find with the sword, hand off to the dagger, strike”. It is this fundamental assumption that I plan to shake to it’s very bedrock.

My local practice has always been firmly in the “we do it by the book” camp, so in preparing for Pennsic I’ve been diving back into the sources to see what they really said. In order to keep this project manageable I’ve decided to focus on the big three Italian rapier authors (Giganti, Fabris, and Capoferro) as that’s what I’m most familiar with as well as they are the most popular sources for the game that we play. If someone else would like to take a look at dall’Agocchie, KDF, or destreza for this, by all means please go right ahead.

Nicoletto Giganti, in his first book published in 1606 has nineteen plays where he has you using sword and dagger.[1] Of those nineteen plays, the only ones where your sword guards their sword are plates 36, 39, 40, and 41. That’s fifteen out of nineteen times where you just cover with the dagger either on the offensive or on the defensive.

Capoferro, in 1610, gives us eighteen plays of sword and dagger. Of those, twelve involve finding first with the sword with the remaining six being ones where he instructs us to just cover with the dagger. Of those six, three are you opening with a feint (bypassing the need to find) with the other three being a defensive pass backward in order to bring the dagger in to play.[2]

Fabris’s 1606 book is a different scale entirely, so the math here is about to get real fun. He spends over twenty plates just describing different guards and what a basic lunge from them might look like. Sometimes he’ll give little pieces of advice about which weapon guards what, but he’s not consistent with it so for our purposes here, I decided to not include that and instead just focus on the plays. Even when a plate had multiple options, for our purposes I only counted it once. The only exceptions were plates 76 and 77 which both use the sword and dagger simultaneously, so I counted those as a point for each category. To further clarify, I counted any play that opened with the winning side either parrying or finding first with the sword as it being the sword that covers. All of the other plates where the first action taken against the opponent’s blade by the winning side was with the dagger I counted as it being the dagger that covers.

For Fabris’s book I, the score comes out as seven plates where the sword was the primary tool for closing out the opponent’s sword and eighteen plays where the dagger was the primary tool. That’s not quite as stark as Giganti, but it’s still a pretty clear picture being painted.

Let’s now take a look at book II. Plate 157 doesn’t have a clear indicator as to which weapon is supposed to close off the opponent’s line, so I didn’t include it as a part of my tally. Same goes for plates 168 and 169. Plate 166 explicitly says to find with both at once, so I counted that as a point for both. Overall we see a lot more plays explicitly saying to find with the sword and then hand the job off to the dagger, as opposed to just defending with the sword while the dagger closes off the line the opponent is most likely to disengage in to. However, the overall picture remains the same. There are eight plates that open with the sword making the first move to control the opponent’s blade and thirteen plates where the job is left up to the dagger.

While you can clearly still initiate with either the sword or the dagger, the literature over all seems to have a clear bias that isn’t what our “by the book” fencers tend towards four centuries later. Why might this be the case? It comes down to 19th century political squabbles and training modalities.

Back in 1880 there was a political squabble between northern and southern fencing masters in the newly formed Italian state. The Italian government had decided to appoint Masaniello Parise, a Neapolitan fencing master, as the chief instructor for the national school. Jacopo Gelli, a northerner and follower of Giuseppe Radaelli’s teachings on fencing, did what so many do in order to prove his point. He looked back to history and hyped up someone far beyond their status in their own lifetime as the pinnacle of what it means to engage in swordplay.[3] The result is that when fencing in the SCA really began to blossom, followed by HEMA, one of the very first sources to be translated was Capoferro’s.

The other reason is what most “period” fencers tend to focus on. In both the SCA and in HEMA, most rapierists concerned with doing things by the book tend to focus the majority of their time on single rapier. At the same time, the meta for the SCA’s default “bring your best” tournaments is rapier and dagger. In broad strokes, the result is that the people concerned with the books spend most of their time fighting single and when they do happen to pick up the dagger they naturally see it as a backup to their primary plan of attack/defense. The folks purely interested in tournament success, though, spend most of their time on rapier and dagger as that’s what gets them where they want to go.

At the end of the day, train for whatever brings you the most joy. If you want to quote the book chapter and verse, that’s wonderful. If you’re more concerned with your place on the podium that’s just fine, you too are bringing to life this most wonderful of lost arts. If you specifically want to do Capoferro, that’s also just fine. However, if your primary sources are Giganti, Fabris, or just “Italian rapier” more broadly, maybe it’s time to revisit the default plan we teach folks when they first pick up a dagger.

If you enjoyed this, then you’re in luck. I recently finished the first draft of my next book, “The Annotated Giganti”. I’m just starting to get some collaborators involved in order to provide a running comments section for each and every plate. Getting to read other people’s thoughts on my favorite fencing book of all time is a real treat and I’m looking forward to sharing it with you soon. In the meantime, feel free to go ahead and pick up a copy of my first book, “Bolognese Longsword: For The Modern Practitioner” at FoolOfSwords.com.

If you’re at Pennsic, feel free to hunt me down for some passes/coaching/nerding out. It means a lot when people tell me they’ve read my work and find something of value in it.

I’ve also got two big workshops coming up soon. The first is I’m teaching a two hour, hands on, class on coaching at Midlands Academy of Defense in Champagne, IL on September 6th. http://placeforstuff.net/events/2025/MAD/

I’ll also be teaching a longsword class at the Pferdesdadt Rapier Classic in Ohio on September 13th. https://pferdestadt.midrealm.org/pferdestadt-rapier-classic/

[1] I’m not counting plate 20 as it shows single sword defeating rapier and dagger, nor am I counting plates 30 through 32 as they just show different invitations on their own without being a part of a particular play.

[2] I’m not counting pate 35 as it’s just a single sword feint with your dagger held back and out of the picture. This is essentially the same thing as Giganti’s plate 20, except that you happen to have a dagger in your off hand, which is for all intents and purposes out of frame. As a note, plate 41 starts with a dagger parry, but that’s only performed by the losing side, whereas the winning side just uses their sword, so I’m counting that one as a point for the “find with the sword first” camp.

[3] Tom Leoni, “Ridolfo Capoferro’s The Art and Practice of Fencing”, page xv.