- Fool of Swords Newsletter

- Posts

- Why It’s Harder to Hit Stationary Targets

Why It’s Harder to Hit Stationary Targets

Perception-Action Coupling and the Sundance Effect

When I was a child, one day my parents brought home a copy of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid for us all to watch. For whatever reason the one scene that stood out to me the most wasn’t the glorious shoot out at the end, it wasn’t the bank robberies, wasn’t the train heist, it wasn’t even the bicycle scene. No, the bit that stuck in my mind was where the two outlaws go to look for a job and Sundance is asked to demonstrate his marksmanship.

At first the boss has Sundance stand perfectly still and try to hit a rock on the ground. Sundance misses and the boss begins to walk away. Then Sundance asks if he’s allowed to move and once he gets unstuck from his stance he hits the target right away. As I got older and dove deeper and deeper into martial arts, I noticed the same exact phenomenon happening to me. I call it the “Sundance Effect”. I’d do just fine trying to pull something off in sparring, but when it came to doing it in class against a static opponent, I’d whiff it. For years I thought that this just meant I was compensating during fights with speed, strength, or whatever else people were using that week to dismiss my fight. I thought that getting it in that static drill was what really mattered, not the slop we all do when we’re going full speed. More recently, I’ve been diving deep into the research on sports psychology and coaching. Turns out, my intuition was right. It is easier if everything’s moving.

Alright, I’m gonna hit you with some vocab now. I swear it’s not that bad, we’ll get through it together. Trust me.

The reason it’s easier for both Sundance and myself to hit something once things are in motion is because of a concept called, Representative Learning Design (RLD).[1] Learning how to fight is not a bunch of isolated actions stacked up on top of each other that you should just be learning one at a time. Yes, it is helpful to eat the pie one slice at a time as opposed to all at once. However, teaching folks how to lunge by having them extend their arm twenty times, then lean their upper body twenty times, then step their front foot forward twenty times doesn’t really feel like “fencing”. You’re not eating one slice of the piece. You’re eating butter, then the flour, and then maybe some blueberries.

Instead, we as coaches ought to aim towards creating exercises that are representative of the environment our students are going to be in. Hitting a static target isn’t hitting a moving target on easy mode. It’s a different skill entirely. If instead I move around, using fencing specific footwork and then have my student lunge and try to hit me when they think I’m in measure, now I’m finally serving them up a whole slice of pie. There’s still more to the pie to be had. This measure game doesn’t cover parries, it doesn’t cover feints, it doesn’t go over how to use your dagger. But it’s still recognizably pie as opposed to just a stick of butter.

What’s driving this is another vocab term, Perception-Action Coupling.[2] At its core, the human brain is set up to solve the problems in front of it. There is not one perfect technique that you pull out and insert into whatever situation comes your way. In short, there is no “perfect lunge”. I repeat, there is no perfect lunge. Instead, there is a continuous feedback loop going on in your head where your actions are constantly being adjust to deal with whatever you’re facing.

When you wake up in the middle of the night to walk to the bathroom, there isn’t just a singular motor program for “walk”. Instead, your brain is constantly adapting to how much light there is, whether your kids left some nifty LEGO tripping hazards for you, or how your step changes with your cozy cat bus slippers. How you act is constantly being informed by what you’re perceiving in that very moment. If you try and make the trek without turning the lights on, you are hurting your ability to perceive the situation and thus your ability to properly act (and stay upright) are going to be impinged. If instead your brain worked by selecting a premade “motor program” of walking from your bed to the bathroom, once you made the initial choice it wouldn’t particularly matter what your perception was telling you. As anyone who enjoys maybe a few too many cups of tea right before bed can tell you, getting to the bathroom at 3AM is a lot harder than it should be for a venture you’ve made so many times before.

To further illustrate my point, let us look at the undisputed GOAT in their movement domain.[4]

As someone who grew up just outside of Chicago in the 90’s, even though I didn’t follow sports, there’s still a special appreciation I hold for Michael Jordan. Looking back at how played, he clearly did not have a single program he fires off for how to do a layup. Layups are messy things, particularly when you have to get around two different people who aren’t trying to stop you from landing the shot. Sure, if it’s just you and the basket, you can try and make the same motion work over and over again, but that’s not what it means to play basketball.

In fencing, or any other martial art, your opponent generally isn’t there to help you land a shot. In fact, even if they don’t know what they’re doing, they’re still going to be trying their hardest to shut you down. Sure, we can train for that in lower pressure environments, having people going at 80% speed and limiting their defenses. Once you switch to playing freeze tag, though, you’re now playing a different game.

What do I recommend for my fellow coaches then? Instead of having your students try and practice idealized answers in a vacuum, the pivot I’ve made this past year is to move toward a problem-posing pedagogy.[5] So instead of saying “this is how your lunge needs to look if you don’t want to land a touch”, I now go, “If I approach you with this guard, how might you get a shot in? What about if I come in from another line?”.

Giving people problems appropriate for their skill level not only helps the lesson stick better, it makes fencers into problem-solvers as opposed to solution-receivers. If you keep at it, you’re going to run into opponents that do things no one at your local practice has tried. Maybe you train in an area where everyone uses a refused guard and now you don’t know what to do when someone comes at you with a good solid structure, bullying your sword out of the way. Perhaps you’re used to everyone trying to attack with opposition and now, suddenly, you’re across from someone whose default is to yield around your blade. If all you’ve ever trained is how to perform idealized movements without any resistance, you aren’t going to be prepared for when someone goes off script. Instead, if you help teach them how to solve whatever problem is in front of them, they’ll be much better equipped to solve the next problem on their own when you’re not there to guide them.

Now, you may be thinking you need to start students off with doing lunges in the air and only introduce resistance a few weeks (or months) in. However, what that’s not giving people an easier problem to solve and then slowly introducing in a harder version of the same problem. Instead, it’s having students train for one scenario, setting them up for when none of that transfers when you go live.[6] Raise your hand if something works for you >90% of the time in drills, but then it feels like it only works <10% of the time when you try it for real. The issue isn’t that now you’re doing the same thing, but it’s a little bit harder now. Instead, the skills aren’t transferring because the thing you’ve been training for isn’t the same thing you’re being asked to perform.

If your goal is kata competitions or just martial arts as performance, then keep doing what you’re doing. Those can still be incredibly impressive skills that get you out of the house, give you a nice workout, and help you to build a sense of community. If instead, though, you’re training to be a fighter then you need to be moving like one as early as possible. I know since I’ve made the switch from “Okay, now I’m going to stand here as you find, gain, then lunge” to “We’re going to move around. How can you hit me while closing off the line of my sword?” I’ve seen students get in a week or two what it used to take months to get them to do. Sure, their techniques might not look as pretty, but they’re effective. And honestly, they’re just more fun to practice.

What are your thoughts? How does this ecological approach line up with what you’ve taught? What can you do at your local practice to shift towards a more problem-posing stance?

If this is a topic that excites you, then good news. My upcoming book “A Constraints-Led Approach to Rapier” is going to cover this all in depth, with specific games and constraints I’ve found useful in my own coaching.

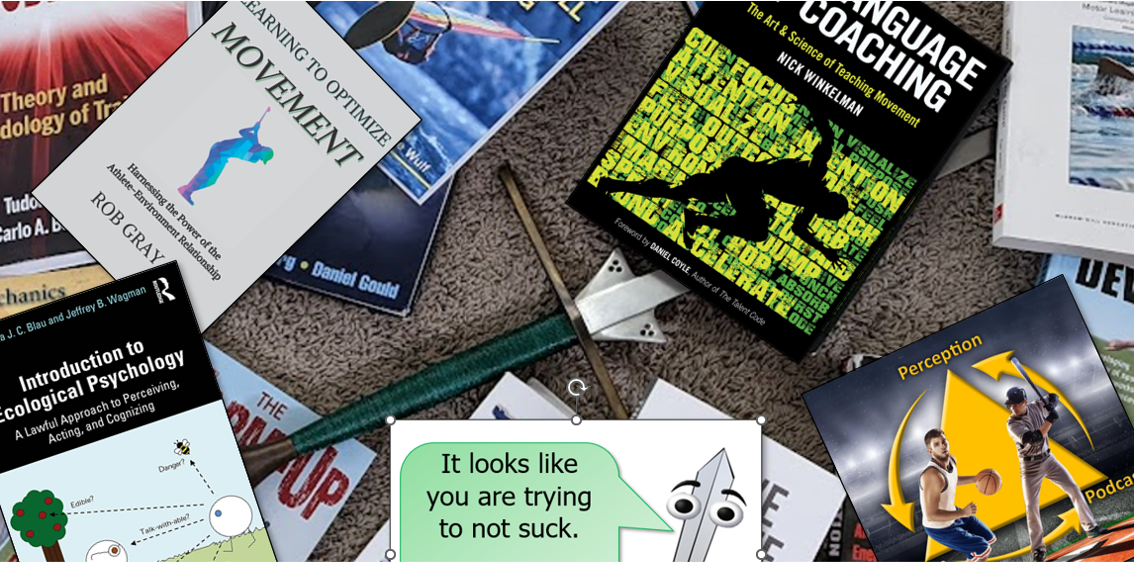

In the meantime, here’s the article that got me started on this crazy journey.

As always, you can pick up a copy of my first book, “Bolognese Longsword for the Modern Practitioner” at FoolOfSwords.com.

[1] Rob Gray, “Learning to be an Ecological Coach”, 74.

[2] You might also see the term “Information-Movement Coupling” used instead.

[3]Joseph Hamill, “Locomotor Coordination, Visual Perception and Head Stability during Running”.

[4] No, I will not be taking any questions.

[5] Paulo Friere “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” 30th anniversary edition, 79.

[6] Gray, 54.